Research Interests

Examining divergence within a species complex of flying lizards

Understanding the forces that drive lineage diversification (i.e., the forces that cause one population/species to become two) has been of interest to biologists since the dawn of the theory of evolution. Indochina is a geographic area located in mainland Southeast Asia that is a megadiverse biodiversity hotspot recognized for its remarkable in situ diversification (i.e., not only are there a lot of species in Indochina, most of them evolved within Indochina), sparking the question: What forces are driving lineage diversification in this region? To answer this question, we examined evolutionary history of a widespread species complex in the context of biogeography, historical taxonomy, and mitochondrial relatedness.

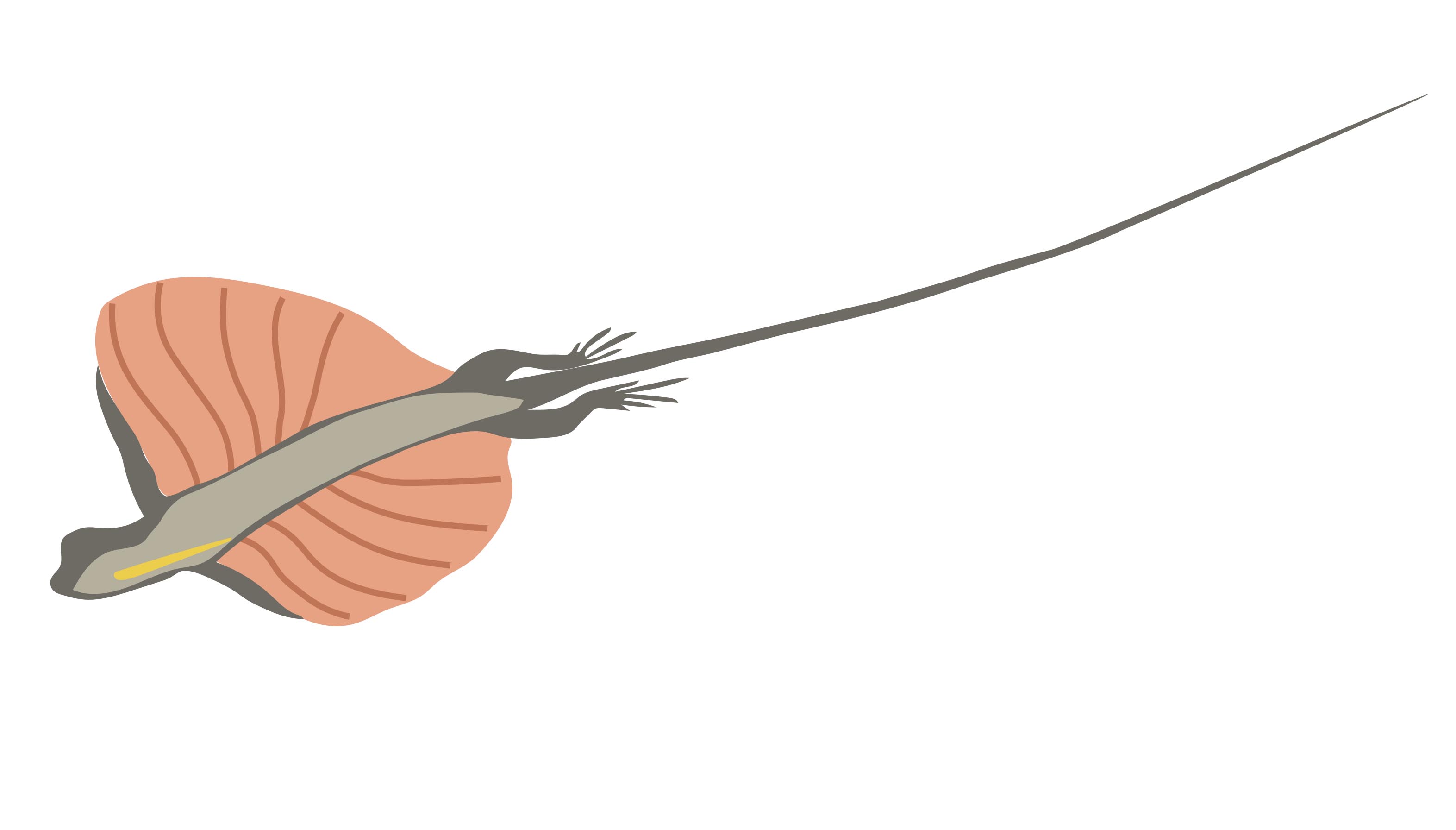

Southeast Asia is home to a unique group of animals: "flying lizards" (genus Draco). The gliding ability of these Agamid lizards make them unique among all vertebrates. Unlike other flyers/gliders, Draco's "wings" (patagia) are attached to ribs which can be extended voluntarily for either gliding or communication. This group of lizards is very species-rich, yet much of the diversity (and the processes driving diversification) remains to be described.

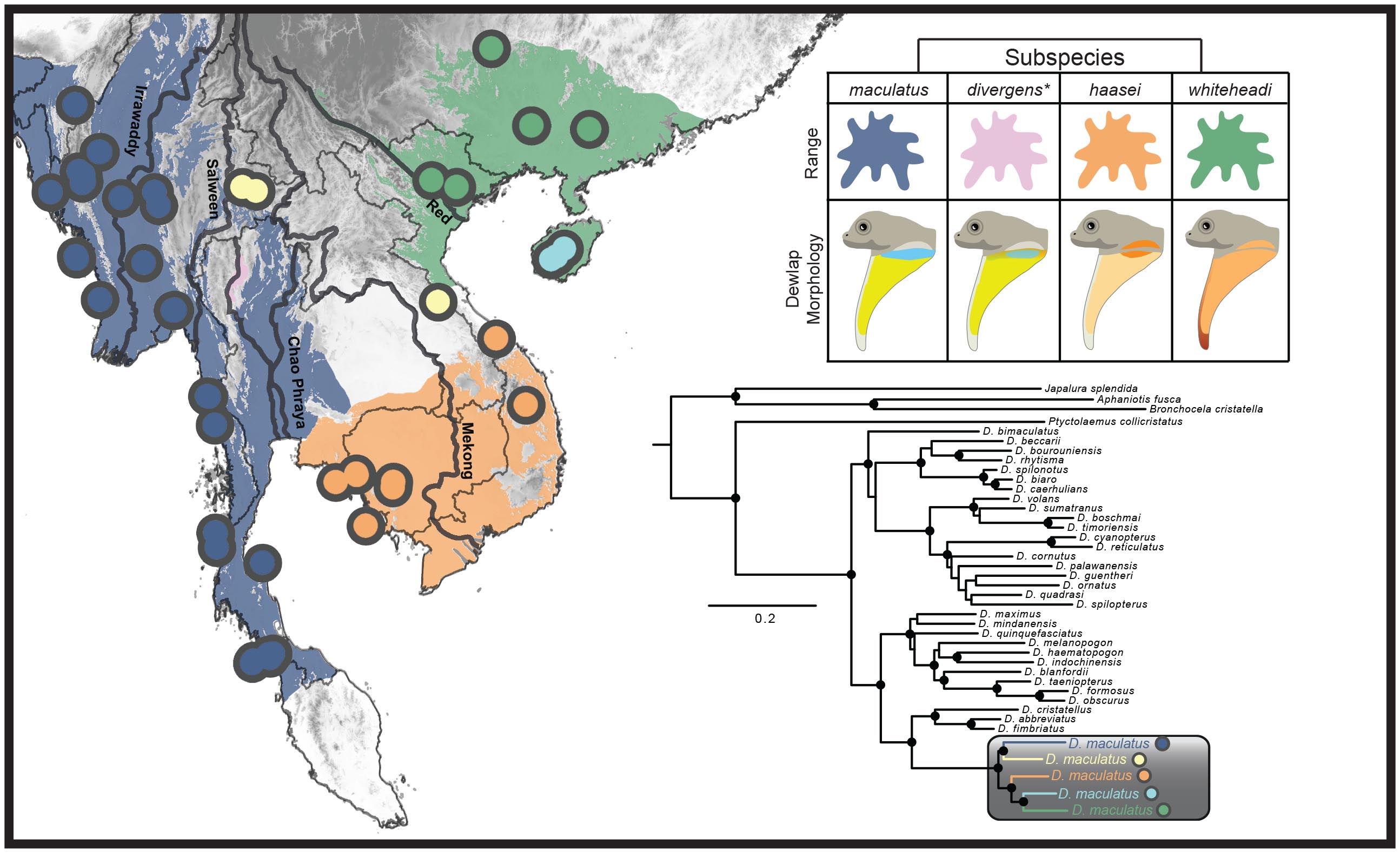

The spotted flying lizard (Draco maculatus) is currently recognized as a single species, but we found that multiple divergent lineages are hidden within this single taxonomic name in a species complex. Large geographic ranges and distinct morphological differences within a taxon recognized as a "single species" can be indicators of a species complex, and D. maculatus possesses both of these characteristics (see map).

We sequenced six genetic regions and assessed the degree of divergence within D. maculatus using maximum likelihood and Bayes factor delimitation. Our findings allude to rivers as potential forces driving speciation within Indochina and indicate that species-level divergence is present within this group (see the publication here: Klabacka et al. (2020) or email me for study details).

Consequences of Asexual Reproduction

As a casual observer of life on earth, you may have noticed that many creatures reproduce by having sex. Because so many organisms "have sex", many people haven't even considered an alternative used for passing genes to offspring. However, evolutionary biologists like to make observations and then ask the questions. As for sex, why have it?

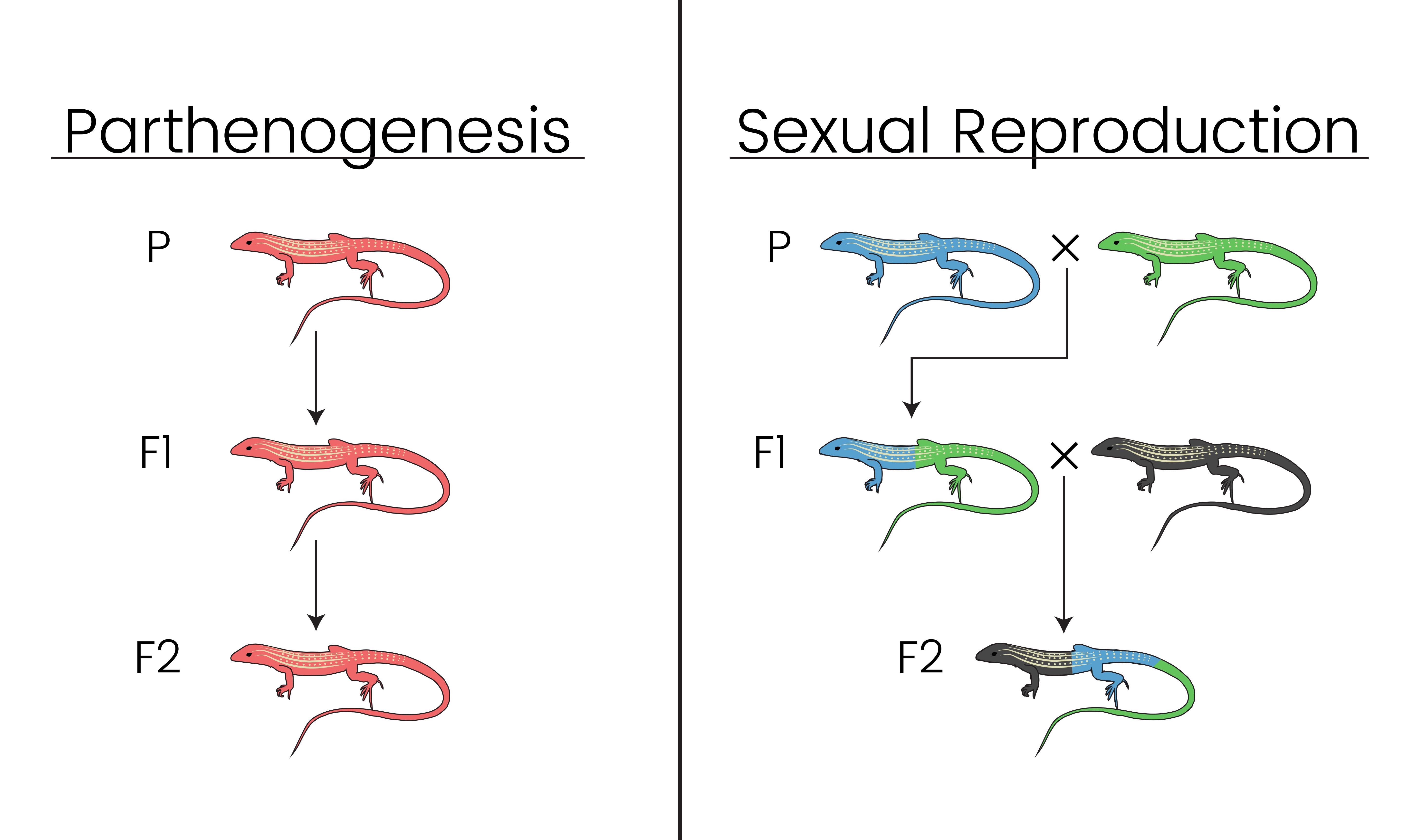

Sex is costly. From a biological perspective, the "purpose of life" is to pass as much of "you" into the future as is possible. Nearly all animals forfeit passing on half of their genetic material for a sexual partner; offspring are made up of ~50% dad's DNA and ~50% mom's DNA. This means if something only has one child, half of their genes hit a dead end. However, sexual organisms with one child do not send half of their genes to the grave, because 100% of their DNA is passed on to offspring (see diagram above).

Another problem if you're a sexual organism is that you have to:

So back to our question: If sex kind of sucks, why have it? Well, to address that question it may be appropriate to ask another: Asexual reproduction sounds nice, but what's the catch? This is a major question within evolutionary biology that I am seeking to address using southwestern whiptail lizards (genus: Aspidoscelis) as a model system. One third of this genus of 40+ species reproduces via parthenogenesis (a form of asexual reproduction wherein no male input WHATSOEVER is needed).

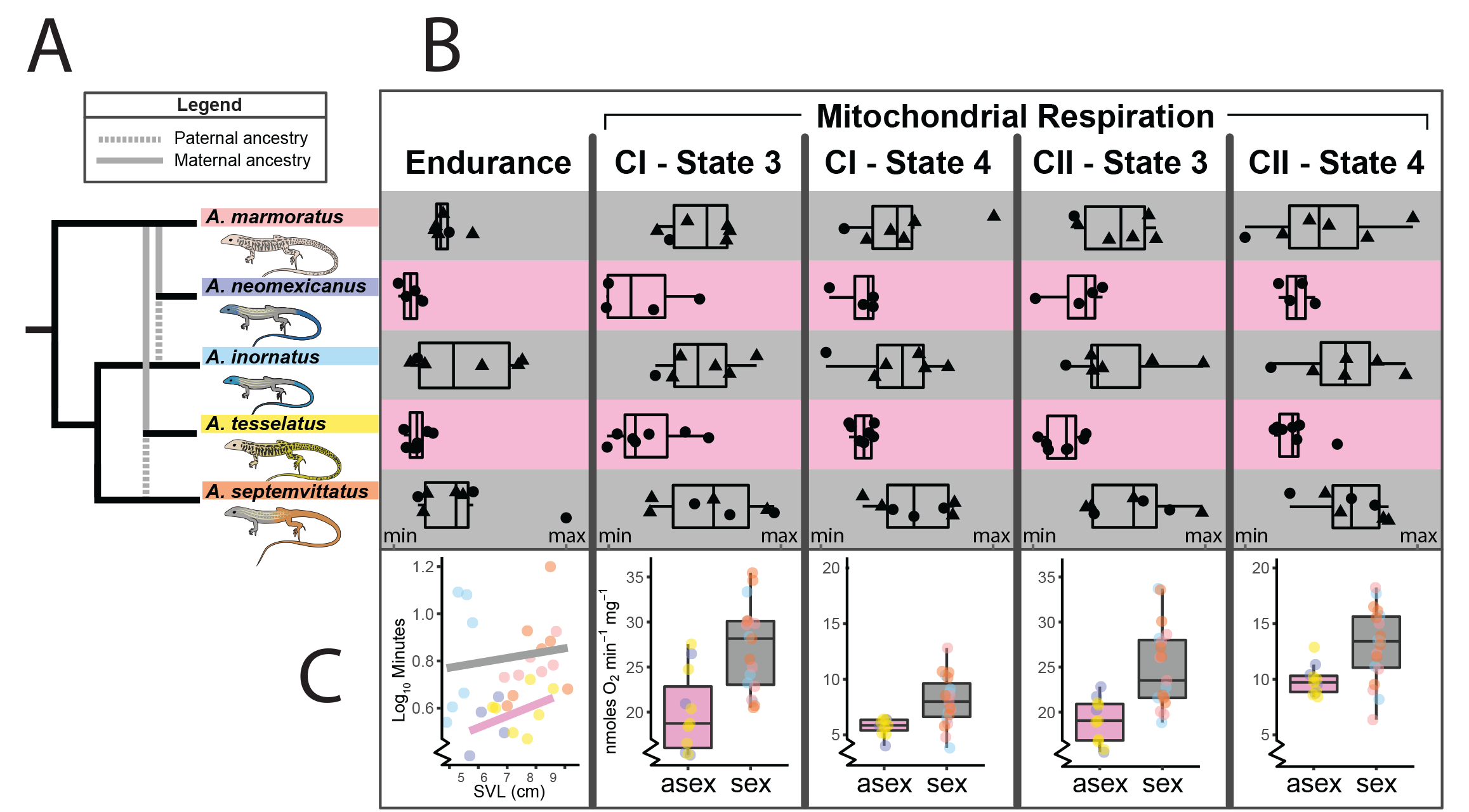

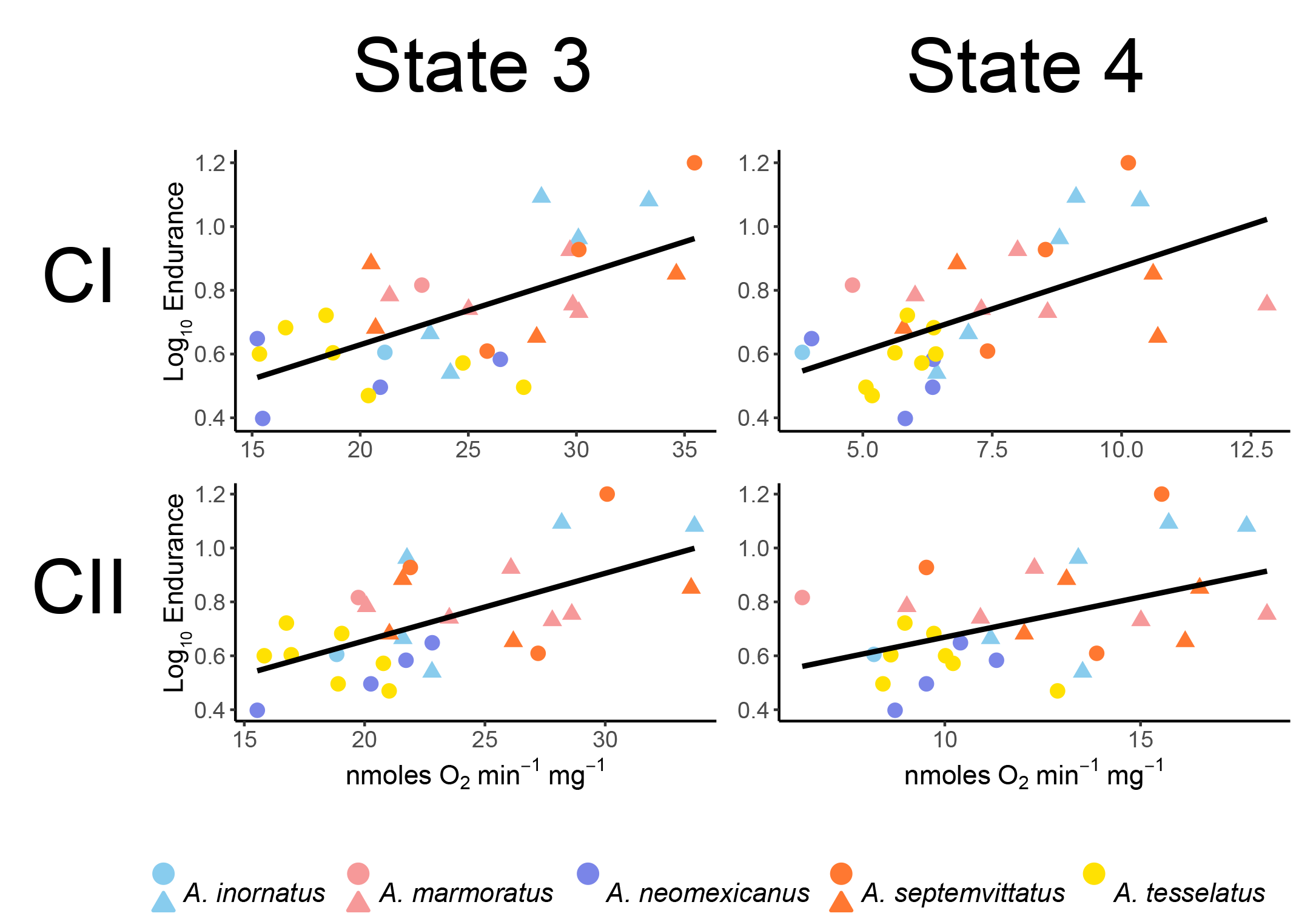

One hypothesis regarding the consequences of asexual reproduction poses that the mitochondria (the cells primary source of energy) experiences reduced function in asexual organisms. This could also affect organism performance where energey demands are high (e.g., aerobic activity). To test this, we measured endurance capacity and mitochondrial respiration in sexual and asexual species of whiptail lizards. We found that asexual species exhibited both (1) reduced endurance capacity and (2) reduced mitochondrial respiration (see figure below for species included in the study and abbreviated results). See publication here: Klabacka et al. (2022), or contact me for a copy.

We also observed a positive association between endurance capacity and mitochondrial respiration. While this may seem intuitive, studies that have involved endurance trials and mitochondrial function have focused on exercise physiology in athletic and biomedical contexts rather than ecology/evolution.

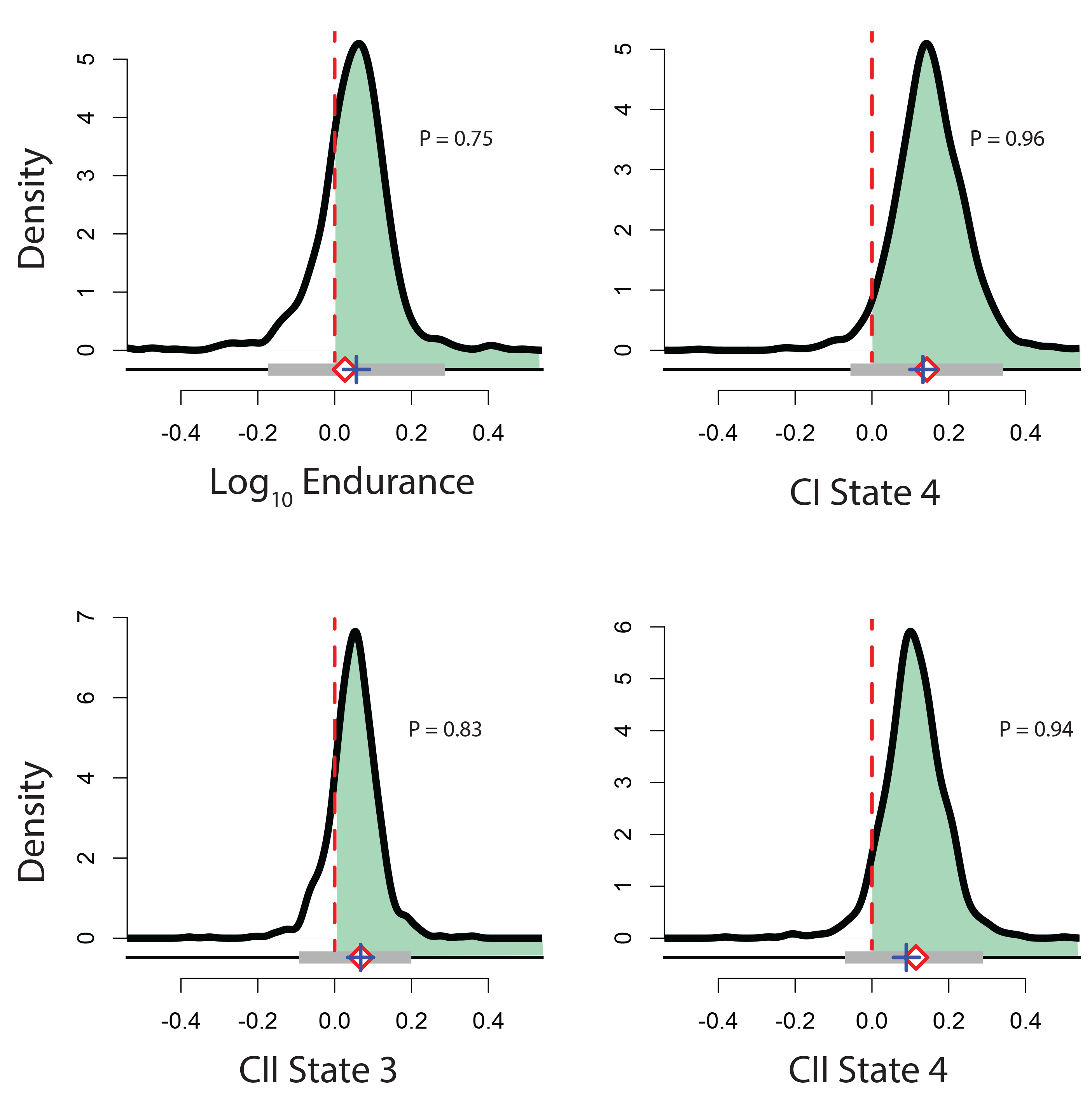

Finally, we quantified variability in the measured phenotypes for sexual parental and asexual hybrid species. We observed reduced variability in asexual hybrid species. This was expected based on the low genetic diversity in asexual populations, and has been observed in other asexual systems. (In the figure below, P = posterior probability that the coefficient of variation is greater in the parental sexual species compared to the hybrid asexual species).

My next project will focus on examining the genetic source for the reduced endurance capacity and mitochondrial respiration in the asexual species using genomic sequencing approaches (funded by an AGA EECG research award).

What drives life history variation in two conspecific ecotypes?

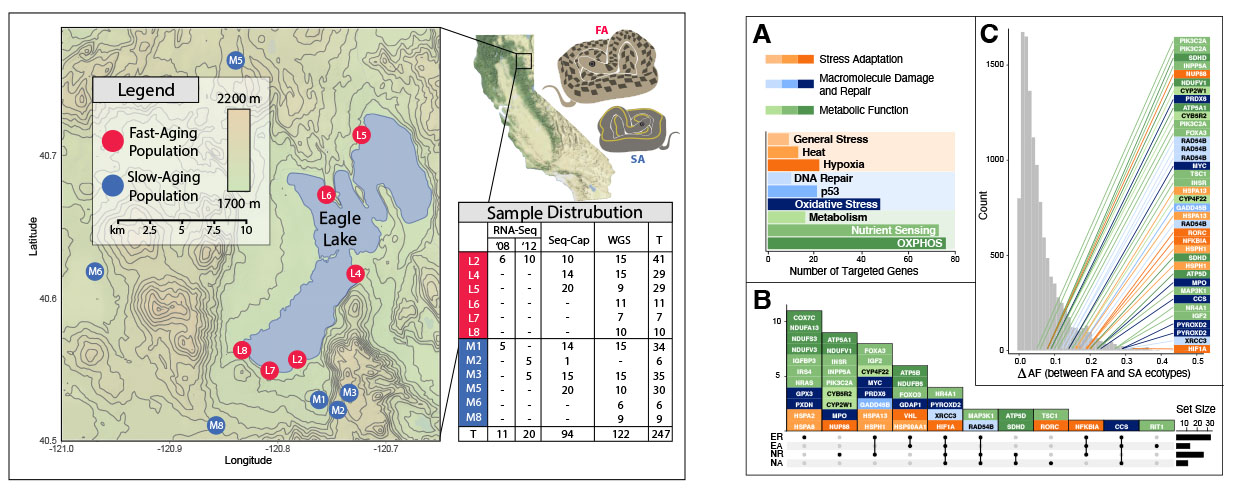

We are examining the genetic underpinnings of divergent phenotypes seen within two ecotypes of western terrestrial garter snake (Thamnophis elegans). Although members of the same species, individuals vary significantly in a number of characters including body size, growth rate, lifespan, rate of senescence, and metabolism. We sequenced genes of targeted genetic networks to examine the role that gene expression and sequence variation play in phenotypic variation.

Using targeted genomic sequencing and population genomic bioinformatic analyses, we identified several genes that exhibit divergence patterns that reflect the morphological and physiological patterns seen in the ecotypes. These genes are located in gene networks involved in growth, reprodouction, and aging, and many of them contain variants that are predicted to have a functional impact on their gene products.